Live Classes

'Strategic play' must guide India in the coming years — reducing the power gap with China, building the capacity to deter Beijing’s aggressive actions on its land and maritime frontiers, and rebalancing the Indo-Pacific.

“India wishes to sit on top of the mountain to watch the tigers fight.” This was the assessment of a Chinese scholar reviewing India’s approach to the unfolding conflict in Taiwan. In a column for the Global Times, Liu Zongyi argues that India will be a major beneficiary if the US can contain China in East Asia and the Western Pacific.

Some Chinese might extend the argument to Europe as well — that the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which began six months ago this week, suits Delhi. The conflict between the Kremlin and the West, they might believe, weakens both sides and would eventually benefit a rising India. There is no doubt that both Russia and the West are wooing India to support them in this conflict.

That kind of hyper-realist Chinese thinking, however, has not been part of India’s strategic culture. In fact, independent India has been far too idealistic. Nothing illustrates it more than Delhi’s enduring illusion of building an “Asian Century” in partnership with Beijing.

At a time when China was isolated in Asia and the world in the 1950s and 1960s, India campaigned with the rest of the world to engage with China. It sought to serenade China before a sceptical Asian audience at Bandung in 1955. Delhi also insisted that Beijing is the rightful owner of a permanent seat in the United Nations Security Council. India pursued for long a “China-first strategy” despite persistent evidence that Delhi’s contradictions with Beijing are structural and not amenable to easy resolution. Delhi’s reluctance to come to terms with that reality has cost India dearly. The Galwan clash two years ago, which followed China tearing apart three decades of peace and tranquillity on the disputed frontier, appears to have made Delhi wiser. It certainly has cured at least parts of the Indian establishment of chronic Sinophilia.

Returning to Liu’s geopolitics, there is no mountain for India to retreat to and watch the US, Russia, and China tear each other apart. In today’s deeply integrated world, great power conflict has systemic effects and consequences for everyone. The Russian war in Ukraine and the Western sanctions in response have roiled global oil markets, disrupted the food supply chains and pushed the global economy into a fresh crisis.

For India, which was just about recovering from the devastating economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, there has been no joy in watching the war in Ukraine. It has no reason to wish for another great power war in the East.

If the current tensions around Taiwan boil over into a shooting war, the global economy will sink even faster and take India down with it. Taiwan’s geopolitical location, its special place in US-China relations, and its centrality to global manufacturing supply chains will make a war in Asia far more consequential than the European one.

Liu argues that “China’s preoccupation with the East China Sea, the Taiwan Straits and the South China Sea”, will reduce Beijing’s “attention toward the Indian Ocean”. “India would take this opportunity to strengthen its maritime power and consolidate its advantages in South Asia and the Indian Ocean region.” That China’s problems on its eastern frontier would open up strategic opportunities for India, however, is a myth. China’s conflict with the US over Taiwan during the late 1950s was also the period when Sino-Indian tensions over Tibet turned into the 1962 war.

China’s growing problems in the Western Pacific over the last decade have not seen any diminution of Beijing’s ambitions in the Indian Ocean. China now has the political will, economic muscle, and growing naval capability to pursue a two-ocean strategy.

There is also an Indian flip side to Liu’s argument — a China locked in a conflict with the US might be more accommodative of India’s concerns. This too has been a persistent but unrealised hope in Delhi. India’s problems with China have less to do with the US policies in Asia, but everything to do with their intractable bilateral disputes.

Sino-US relations have oscillated wildly in the last 75 years, but that has had little impact on the resolution of the clash of Chinese and Indian territorial nationalisms. That problem has been worsened by the growing power gap between Beijing and its neighbours, including India.

Beijing does not believe it must make nice to a Delhi that keeps political distance from Washington. China is convinced it now has the power to redeem its historic territorial claims vis a vis India and other Asian neighbours. Beijing also believes that the West is in terminal decline and the changing Asian balance of power allows China to set the terms of engagement with the US in its own favour.

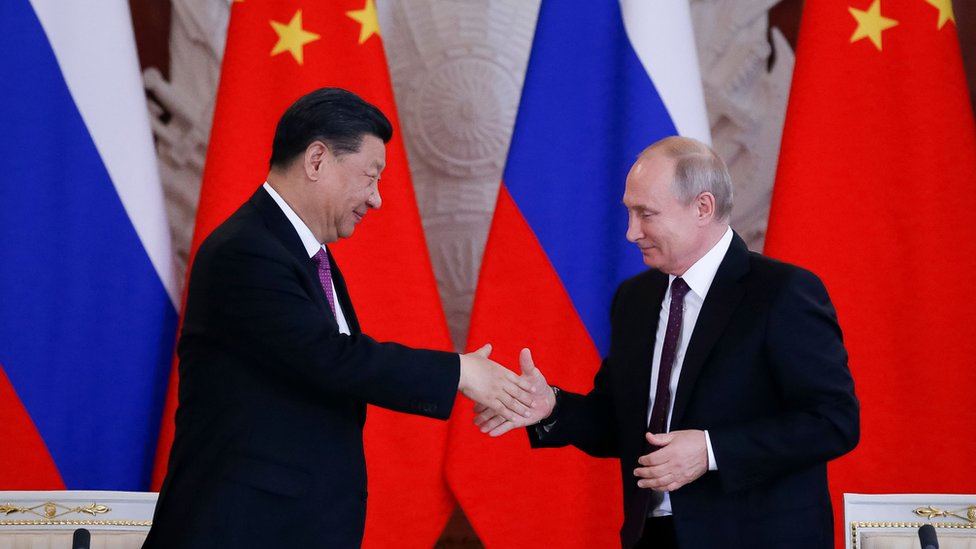

Russia seems to share this assumption with China and the two have now proclaimed an alliance without limits. Like Xi Jinping, Vladimir Putin has bet that a weakened West will be unable to stop the Russian attempt to restructure the European security order. Both Putin and Xi have been hailed for their great “political genius”. But both of them may have over-estimated their own power and under-estimated the resilience of the West.

At the root of this miscalculation may be the kind of geopolitical thinking articulated by Liu Zongyi. Six months after the invasion of Ukraine, it is difficult to see how Putin’s Russia can come out victorious, whichever way Moscow defines “victory”. Xi’s China too will find it hard to emerge unscathed from an escalating confrontation with the US.

In Europe, the Russian aggression has compelled Finland and Sweden to join the US-led NATO. Putin has also put an end to Germany’s neutralist temptations. In Asia, Japan has embarked on its own rearmament and is strengthening its alliance with the United States and is eager to build regional coalitions against China.

Unrealistic external calculus and an authoritarian political bubble at home have seen Putin and Xi squander their national gains over the last three decades. The costs of overweening geopolitical ambitions in Moscow and Beijing are just coming into sharp relief.

Although it is widely assumed that Putin and Xi are now rulers for life, it is unrealistic to ignore the pro-Western tendencies so deeply rooted in modern Russian and Chinese political tradition. “Westernisers” in Moscow and Beijing may be down right now, but they have not disappeared.

Liu Zongyi’s suggestion that Delhi can sit back and watch the great powers bleed each other imputes the Chinese way of thinking to India. Delhi, however, must find its own way to manage the current turbulence in the triangular relationship between Washington, Moscow, and Beijing.

A better appreciation of past errors in misjudging the frequent shifts in great power relations should help Delhi more adroitly navigate the current dynamic. The discourse on India’s current diplomacy focuses on Delhi’s “positional play” among the great powers. But there is no mistaking the essential “strategic play” that must guide India in the coming years — reducing the power gap with China, building the capacity to deter Beijing’s aggressive actions on its land and maritime frontiers, and rebalancing the Indo-Pacific.

Paper- 2 (International Relations)

Writer - C. Raja Mohan (senior fellow, Asia Society Policy Institute, Delhi)

Download pdf to Read More