Live Classes

The difficulty in getting jobs and inflation were the two major issues that played a role in the results of the Lok Sabha Elections 2024, according to the Lokniti-CSDS pre-poll survey (The Hindu, April 11, 2024). The India Employment Report (IER) 2024, published by the Institute for Human Development and the International Labour Organization, also illustrated a rise in the unemployment rate from a little more than 2% in 2000 and 2012 to 5.8% in 2019. Unemployment reduced somewhat to 4.1% in 2022, although time-related underemployment was high at 7.5%. The labour force participation rate (LFPR) also fell from 61.6% in 2000 to 49.8% in 2018 but recovered halfway to 55.2% in 2022. But in this gloomy picture marked by unemployment and underemployment, there was a steep and steady upward trend of female LFPR from 24.6% in 2018 to 36.6% in 2022 in rural India. It also increased by around 3.5% from 20.4% in 2018 in urban areas. This is in contrast with male LFPR, which rose marginally by 2% in rural areas and almost stagnant in urban areas.

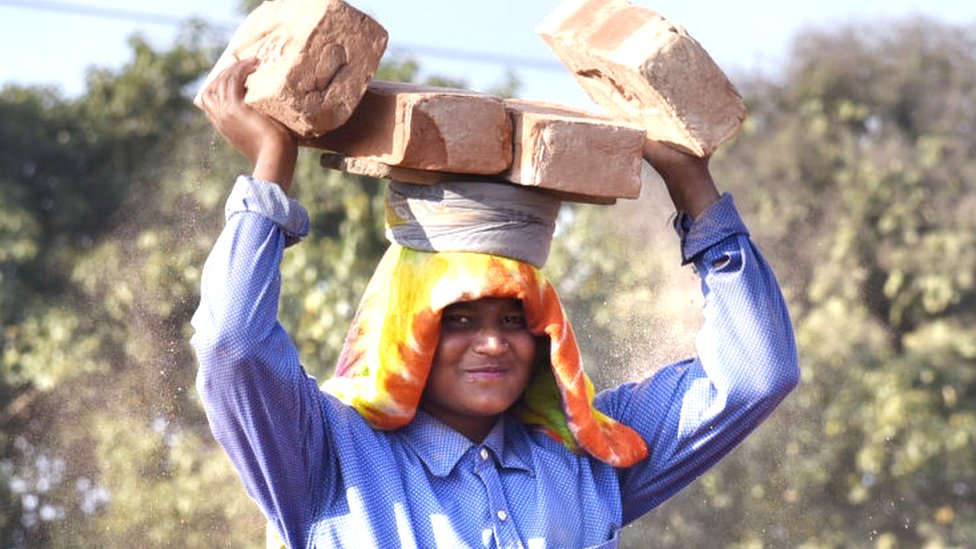

Female LFPR in India is low when compared to the world average of 53.4% (2019), and it has decreased from 38.9% in 2000 to 23.3% in 2018. Against this backdrop, the current increasing trend in female LFPR, especially a 12% rise in rural India during 2018-22, indicates an untapped opportunity for employment generation. Women have been engaged in unpaid family labour work in both rural and urban areas. While 9.3% of males were employed as unpaid family workers, the same was as high as 36.5% for females in 2022. Moreover, the difference between female and male unpaid family labour employment was 31.4% in rural areas against only 8.1% in urban areas. Hence, if appropriate strategies are taken, there is a much greater opportunity for female employment generation, especially in rural areas.

The choice of employment for earnings may be extremely gendered, which makes generating employment opportunities for females tricky. Our study on work conditions and employment for women in the slums of Bhuj, Gujarat, shows that women are more interested in engaging in traditional employment activities from home, such as bandhani, embroidery and fall beading, rather than other opportunities, including non-farm casual labour. The flexibility of work and the possibility of working from home were the major reasons for preferring traditional occupations despite their low income. The study also found that 30% of women were stuck to their traditional occupations due to the unavailability of other options. A lower rise of female LFPR in urban than rural areas during 2018-22, as shown in IER 2024, also indicates a lack of appropriate and gainful opportunities for females in urban areas. The opportunity to develop one’s own enterprise was difficult due to limited access to capital and binding social norms where males of a particular community control the dominant business of the locality — tie and dye. Collectivising women under self-help groups (SHG), and, further, through federations may benefit women involved in traditional occupations. SHG women may be trained to acquire new skills, and federations may link women directly to the market for better returns. The Kutch Mahila Vikas Sangathan (KMVS), a local non-profit organisation, is working in the region towards this end.

Traditional occupations are accepted by society as they conform to local gender norms. These occupations have emerged as the dominant choice of women. Traditional occupations support women’s practical gender needs, such as managing both household work and earnings. However, they may not help in meeting strategic gender needs, such as challenging regressive gender norms. Moving out of their own dwelling and working in a professional environment increases women’s agency and empowers them to meet strategic gender needs.

The importance of market access

The foray of women into male-dominated workspaces would increase competition for labour work. This competition can be avoided by generating new opportunities in previously neglected arenas. In a study on the relationship between the type of dominant irrigation source of a region (canal or groundwater) and women’s empowerment (farm employment and decision-making abilities) in the villages in the Upper Gangetic Plains of Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh, we found that women’s wages in farm labour work and decision-making abilities increased with the expansion of relatively less dominant source of irrigation and vice versa. Males may take more interest if more water is available through the dominant source of the region. Further, the expansion of canal irrigation during Ziad (summer slump season), when males had less interest in agriculture, positively affected female empowerment.

Additional non-conventional irrigation benefits women, as this writer’s recent field visits to villages in West Bengal showed. Women have initiated farming, pisciculture, nursery and vermicompost after water is made available through ponds or tube wells in arid and monocropped regions. These women are part of an all-women water user’s association supported by the West Bengal Accelerated Development of Minor Irrigation Project, Government of West Bengal. Availability of work near home has reduced female migration with the whole family and has increased family welfare. Male family members help in heavy activities that demand strength, such as ploughing or netting in ponds. In most tribal villages, women are barred from ploughing due to gender norms. Similar norms exist for netting in ponds. Women said that they could carry on without the help of male family members if they used hired tractors for ploughing and hired labour for netting. More market interaction empowers women by enabling them to circumvent gender norms and reduce dependency on male family members. Far away, in the Upper Gangetic Plains, a more vibrant water market was found to be associated with higher agency by women to influence the purchase of agricultural inputs.

The earnings of both men and women contribute to family income and welfare. Hence, the strategy to enhance women’s workforce participation and reduce underutilisation of time can be possible by developing income-earning opportunities where males need not be confronted and driven out of the labour market. Women’s work opportunities at or near home can enhance the family income and women’s position in the family. Strikingly, a woman in West Bengal was proud that she could lend money to her husband to buy agricultural inputs. In another study in the slums of Kolkata, it was observed that women’s participation in the workforce has reduced economic vulnerability and improved resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Need for a better work environment

At the same time, participation in work outside the home should be focused. This has a more direct impact on women’s empowerment. However, a long-term strategy is required to develop a better work environment for women. Safety and basic facilities in the workplace (toilets and crèches) should be made available. Public policy should mandate these facilities in small- and medium-manufacturing or business units.

A strategy of focusing on the improvement of female LFPR would improve overall employment and the family income. In rural areas, public policy should help women by providing more access to resources (such as water) and markets (to buy inputs and implements and to sell produce). In urban areas, better facilities in the workplace should be mandated. Collectivising women and federating collectives in rural and urban India under planned economic activities will be most helpful. The Lakhpati Didi programme aiming at raising an SHG woman’s annual income to ?1 lakh or above may pave the way

Download pdf to Read More